No one likes to be reminded that their largest organ is a veritable menagerie of microbes. But Parallel Health turns the skin microbiome from creepy fact to potentially transformative skin care by engineering a custom cocktail of phages and siccing them on the bacteria that cause acne and other conditions.

Parallel Health emerged from stealth today at TechCrunch Disrupt as part of the Startup Battlefield, revealing (beyond their existence) $2.3 million in pre-seed funding and a first product, a custom phage therapy skin serum.

The company got its start out of a project at a larger cosmetics company, where they were attempting to prove the efficacy of phage therapy to treat chronic skin conditions. The team found that some people benefited profoundly and others not at all, and concluded that what was needed was a serum with phages customized just for the user. This veered too deep into biotech for the parent company, so Natalise Kalea Robinson and Nathan Brown ended up founding Parallel to pursue the idea.

A word on phages. These things — they’re not alive, Brown made clear — are basically viruses that target bacteria and are perfectly safe and naturally occurring. In fact, they were a promising treatment method in the early 20th century before antibiotics were discovered; even after penicillin (far more effective at the time) was discovered, some places continued their research into what you might call bacteria’s nemesis.

But recently, as antibiotic-resistant strains of staphylococcus and tuberculosis gain ground and force ever more diverse treatment methods, that phage therapy has seen a resurgence of interest. And it was that which drove the experiment that led to Parallel Health’s founding, though a number of other factors influenced their approach.

For one thing, dermatology is an established science, but it’s one of many fields where cheap, fast genetic sequencing is set to make serious inroads. What lives on our skin? We have a general idea, for sure: a set of bacteria and other microbes in our pores, follicles, under our nails — it’s not pleasant to think about, but it’s the truth. We’re walking ecosystems, and we can fall out of equilibrium (though “natural balance” is an exaggeration) by something as simple as adopting a dog or moving in with a partner.

“Dermatologists are flying blind,” said Brown. “They’re using antibiotics in an empirical way: they try one, and if it doesn’t work, they try another. We need to start looking at the microbiome in combination with phenotypes [i.e., visible characteristics].”

Just one problem: No one actually knows what the skin microbiome is “supposed” to look like. After some initial data collection to prove out the idea, said Kalea Robinson, “when we compared all of the microbes that we had to the public databases, 90% of what we cultured was novel.”

“No one knows what the microbiome looks like on average! We had to go out and recruit people from all across the U.S., 18 to 87, men and women, from all ethnicities, from every state, and have them swab their face and body,” she continued. “From there we started to look for patterns, and we developed our own bioalgorithms. We tried to be as broad as possible, because no one has done this before — it’s part art and part science.”

“This took a long time, by the way,” she added.

What they learned from this data allowed them to define eight general skin types that are specific enough to allow them to be treated individually but different enough that a treatment for one won’t work on another. Factors include bacteria overgrowth, the presence or absence of certain beneficial or harmful species, levels of hydration, a “diversity score” (meaning more types of microbes), and so on.

“I think we could have done 100 types, but it doesn’t really make sense as a consumer product. Eight is true to the data but feels approachable as a patient,” Kalea Robinson explained.

Image Credits: Parallel Health

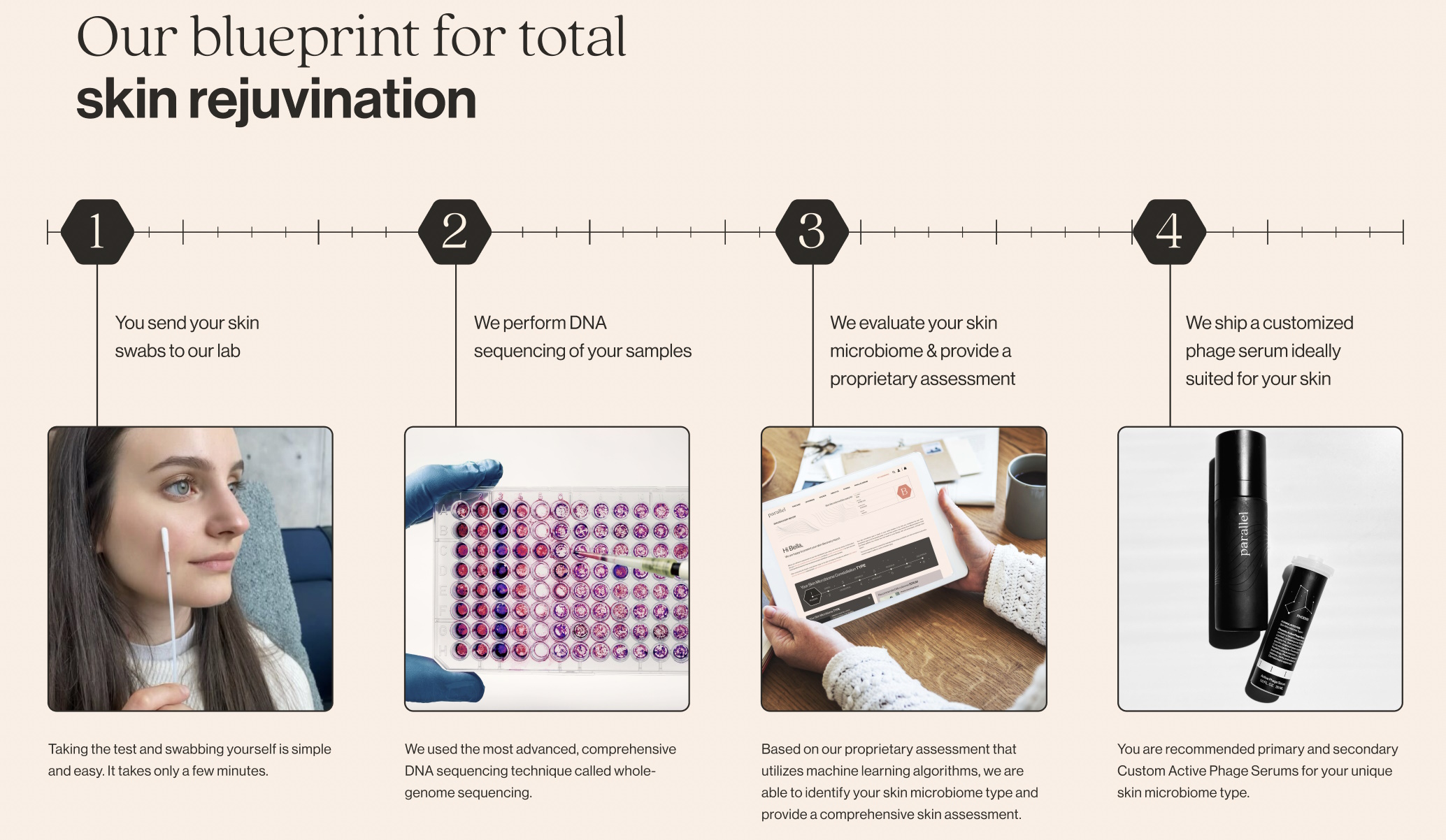

The service they offer, then, is this: You get a testing kit and swab your face, then send it in. They use a “proprietary automated process” to analyze it (via sequencing giant Illumina), putting you in one of the eight types, after which you receive the serum infused with phages engineered to attack the bad bacteria in that category. Brown noted that there’s no CRISPR or other high-tech bioengineering required, saying, “It’s totally unnecessary.” (Incidentally, additional or more specific serums can be produced, but that’s more of a niche case.)

The catch — and part of what has made treatment of skin problems so difficult in the past — is that your microbiome changes both regularly and spontaneously. You likely have a different type in the summer and winter, for instance, but you may acquire a different type if you move in with someone, or start playing a sport, or go swimming a lot. So users would take the test every six months or so or until a pattern is recognized.

As the company provides this service, it builds a library of novel data around the microbiome. This will inform their own product and research, perhaps leading to more and better options, but it’s also just fundamentally interesting to science, since no one has done this kind of long-term, lateral testing before.

“When the doctors first hear about it, they’re skeptical, but when they look into the scientific literature, they find more than they expected. Like, Staphylococcus aureus is involved in lymphoma. It’s just a matter of looking,” said Brown. “Using the test, we can figure out unknown unknowns, so we can improve people’s understanding of their own systems as well as the medical corpus.”

That could be useful beyond the world of cosmetics and treating common maladies — though the founders were clear that there is no plan yet, outside some talks to license certain phages, to dive deeper into the therapeutic side of things.

“We do recognize that there’s interest there,” said Kalea Robinson. “We were approached for acquisition before we were a year old, for our data. But we want to be responsible with the data — it’s our moat for now.”

The company’s site and service is now live, and they’re taking orders to ship as soon as possible — tomorrow, if you’re on the short end of the thousands of people who have signed up on the waiting list.